Before I get to Mao’s Cultural Revolution, I want to point out a few of Mao’s achievements. In the “Land of Famines”, China’s last famine was in 1958-62. For the first time in China’s long history, there hasn’t been a famine since 1962, fourteen years to Mao’s death in 1976 and another forty-two years since then.

The Mao era started in October 1949. Mao said the People’s Republic of China would be free of inequality, poverty and foreign domination. The population of China was 541,670,000. Women were given new rights at work and in marriage, and foot binding was abolished. To deal with disease, Mao launched programs to improve health care that never existed before, and most of the people were inoculated against the most common diseases. When Mao died, the average life expectancy had increased from 35 to 55, and it is now 76.

When Mao died, the population had increased to more than 700,000. Extreme poverty had been reduced by about 14 percent. Since his death, poverty was reduced to where it is today at 6.5 percent of the population.

With a poverty rate of about 95-percent, Mao had promised land reforms to divide the land more equally. In 1950, with Mao’s blessing, rural property owners were judged enemies of the people by the rest of the rural people and hundreds of thousands were executed for their alleged abuses and crimes against the people that denounced them.

Soon after discovering that the famine was real, Mao ended the Great Leap Forward and publicly admitted he had been wrong and stepped aside to let someone else run the country. The large communes were abandoned, and the peasants returned to their villages and were given land again. At the time, Mao was popular with the people but he still resigned as the head of state.

Then Mao wrote his infamous “Little Red Book” and used it to start the Cultural Revolution.

Zhang Baoqing, an early Red Guard member in Beijing, said, “Chairman Mao started the Cultural Revolution (1966 – 1976) to keep up the momentum for change. We thought if we followed Mao, we could not go wrong.”

Millions, mostly teenagers, willingly followed Mao’s advice.

The Cultural Revolutions stated goal was to preserve ‘true’ Communist ideology in the country by purging remnants of capitalist and traditional elements from Chinese society and to re-impose Mao Zedong Thought as the dominant ideology within the Party.

Britannica.com says, “Mao pursued his goals through the Red Guards, groups of the country’s urban youths that were created through mass mobilization efforts. They were directed to root out those among the country’s population who weren’t ‘sufficiently revolutionary’ and those suspected of being ‘bourgeois.’ The Red Guards had little oversight, and their actions led to anarchy and terror, as ‘suspect’ individuals—traditionalists, educators, and intellectuals, for example—were persecuted and killed. The Red Guards were soon reined in by officials, although the brutality of the revolution continued. The revolution also saw high-ranking CCP officials falling in and out of favor, such as Deng Xiaoping and Lin Biao.

“The revolution ended in the fall of 1976, after the death of Mao … The revolution left many people dead (estimates range from 500,000 to 2,000,000), displaced millions of people, and completely disrupted the country’s economy.”

Return to or Start with Part 1

中

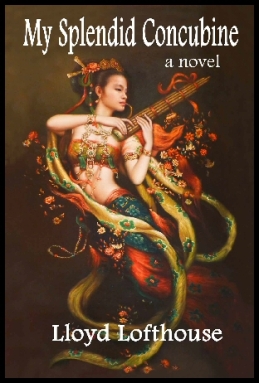

Lloyd Lofthouse is the award-winning author of My Splendid Concubine, Crazy is Normal, Running with the Enemy, and The Redemption of Don Juan Casanova.

Subscribe to my newsletter to hear about new releases and get a free copy of my award-winning, historical fiction short story “A Night at the Well of Purity”.

Posted by Lloyd Lofthouse

Posted by Lloyd Lofthouse