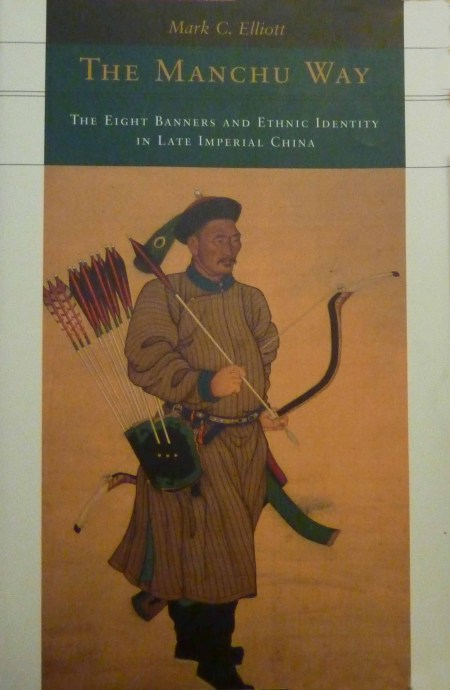

I have a book on the elite troops of China’s Qing Dynasty, and used The Manchu Way for research (along with lots of other work) while writing My Splendid Concubine and Our Hart. I spent from 1999 to late 2007 researching, writing, revising, editing and rewriting the manuscript.

I wanted 19th century China to come alive and be another character in Hart’s Concubine Saga.

Mark C. Elliott wrote The Manchu Way. I was attending a NCIBA Trade Show in Oakland, California several years ago and met Elliott. When I expressed interest in the book due to my project, he gave me a copy.

History Today said of Elliott’s book, “This is a wide-ranging and innovative book. Furthermore, it is written in a lively, accessible style… Overall, it is undoubtedly a scholarly achievement of the highest order.”

I was fortunate to have this resource while writing of Robert Hart’s early years in China. In fact, Hart was the only foreigner the emperor trusted and Hart worked for Qing Dynasty for most of his life.

The Qianlong emperor (pronounced “chien-lung”) was the fourth monarch of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) who reigned from 1736 to 1795.

The four-minute video starts by saying that during the reign of the Qianlong Emperor there were several rebellions in Sichuan province.

The Qing banner armies fought wars against the Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Kyrgyzs, Evenks and Mongols. Unsuccessful costly wars were also fought with Vietnam and Myanmar.

Although millions of square miles or kilometers were brought into the empire, the strain on China’s treasury and military due to casualties and deaths resulted in a military decline.

This decline contributed to China’s weakness a few decades later when the British Empire and France invaded China to force the Qing Dynasty to allow opium to be sold to the Chinese people and give missionaries total freedom to convert the population to Christianity, which caused more wars and tens of millions of deaths during the 19th century.

The Qing army was divided into eight banners. Each banner had its own color scheme, which was reflected in their clothing, armor and flags. There were eight Manchu banners, eight Mongolian banners and eventually eight Han Chinese banner armies for twenty-four armies. In 1648, there were between 1.3 and 2.44 million people in the Chinese, Manchu and Mongol Banner armies. By 1720, the numbers were estimated at between 2.6 and 4.9 million.

China has a history of maintaining large armies for more than two thousand years mostly for defense.

Discover China’s Greatest Emperors

______________

Lloyd Lofthouse is the award-winning author of the concubine saga, My Splendid Concubine & Our Hart. When you love a Chinese woman, you marry her family and culture too.

If you want to subscribe to iLook China, there is a “Subscribe” button at the top of the screen in the menu bar.

Posted by Lloyd Lofthouse

Posted by Lloyd Lofthouse