A review of “Behind the Red Door” by Richard Burger

A review of “Behind the Red Door” by Richard Burger

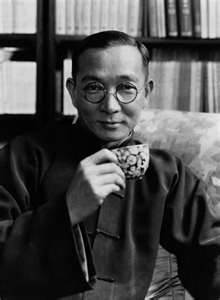

Review by Tom Carter

Among the many misimpressions westerners tend to have of China, sex as some kind of taboo topic here seems to be the most common, if not clichéd. Forgetting for a moment that, owing to a population of 1.3 billion, somebody must be doing it, what most of us don’t seem to know is that, at several points throughout the millennia, China has been a society of extreme sexual openness.

And now, according to author Richard Burger’s new book Behind the Red Door, the Chinese are once again on the verge of a sexual revolution.

Best known for his knives-out commentary on The Peking Duck, one of China’s longest-running expat blogs, Burger takes a similar approach to surveying the subject of sex among the Sinae, leaving no explicit ivory carving unexamined, no raunchy ancient poetry unrecited, and, ahem, no miniskirt unturned.

Opening (metaphorically and literally) with an introduction about hymen restoration surgery, Burger delves dàndàn-deep into the olden days of Daoism, those prurient practitioners of free love who encouraged multiple sex partners as the ultimate co-joining of Yin and Yang. Promiscuity, along with prostitution, flourished during the Tang Dynasty – recognized as China’s cultural zenith – which Burger’s research surmises is no mere coincidence.

Enter the Yuan Dynasty, and its conservative customs of Confucianism, whereby sex became regarded only “for the purpose of producing heirs.” As much as we love to hate him, Mao Zedong is credited as single-handedly wiping out all those nasty neo-Confucius doctrines, including eliminating foot binding, forbidding spousal abuse, allowing divorce, banning prostitution (except, of course, for Party parties), and encouraging women to work. But in typical fashion, laws were taken too far; within 20 years, China under Mao became a wholly androgynous state.

We then transition from China’s red past into the pink-lit present, whence prostitution is just a karaoke bar away, yet possession of pornography is punishable by imprisonment – despite the fact that millions of single Chinese men (called bare branches) will never have wives or even girlfriends due to gross gender imbalance.

Burger laudably also tackles the sex trade from a female’s perspective, including an interview with a housewife-turned-hair-salon hostess who, ironically, finds greater success with foreigners than with her own sex-starved albeit ageist countrymen.

Western dating practices among hip, urban Chinese are duly contrasted with traditional courtship conventions, though, when it comes down to settling down, Burger points out that the Chinese are still generally resistant to the idea that marriage can be based on love. This topic naturally segues into the all-but-acceptable custom of kept women (little third), as well as homowives, those tens of millions of straight women trapped in passionless unions with closeted gay men out of filial piety.

Behind the Red Door concludes by stressing that while the Chinese remain a sexually open society at heart, contradictive policies (enforced by dubious statistics) designed to discard human desire are written into law yet seldom enforced, simply because “sexual contentment is seen as an important pacifier to keep society stable and harmonious.”

____________________________

Travel Photographer Tom Carter traveled for 2 years across the 33 provinces of China to show the diversity of Chinese people in China: Portrait of a People, the most comprehensive photography book on modern China published by a single author.

Also by Tom Carter Eating Smoke — a question and answer with author, Chris Thrall in addition to Harlequin Romance Invades China

If you want to subscribe to iLook China, there is a “Subscribe” button at the top of the screen in the menu bar.

Note: This guest post by Tom Carter first appeared in China in City Weekend Magazine. Reblogged with permission of Tom Carter. Behind the Red Door was published by Earnshaw Books

Posted by Lloyd Lofthouse

Posted by Lloyd Lofthouse

A review of “

A review of “